The Best of Youth

Earlier this year I was roaming around Netflix and deciding on a movie to spend an evening streaming. I came across a film that sounded fairly ambitious titled The Best of Youth. It was described as a sprawling drama that tracked the lives of two Italian brothers (Nicola and Matteo) from the summer of 1966 to 2003. I checked out the rating on Rotten Tomatoes: 95% of critics approved and 98% of audiences. I also found out it left France winning the 2003 Cannes Film Festival. I was intrigued. The only thing that worried me was that the term ‘sprawling epic’ was not only for the decades the film covered but also its running time. It covers just over 6 hours and when it was originally released in movie theaters around the country it was split up into 2 separate showing with an intermission in between. Yet the reviews pulled me in with critics universally saying that it ‘earned every minute’. So I pressed play and I can happily say when I watched the credits roll after that six hour viewing (with a couple of intermissions in between) I can emphatically state that this is the most important film Italy has produced since the age of Fellini.

Now, this installment of Honestly Italy will not be a film review. I will leave that to the professionals. Instead, I will use the film as a springboard to explain three important eras in modern Italy that act as backdrop for much of the movie. The Best of Youth was originally screened in front of Italian audiences that knew very well the historical background under which the film was operating. It was a very recent history that created the country we know today. The film can be viewed and enjoyed purely as a character piece without much investigation into the events of past Italian decades. But by understanding the backdrop of this family drama one can have a fuller, more complete enjoyment of The Best of Youth.

There are three distinct and fascinating eras covered in the film. We will breeze through each era from the summer of 1966 when the film starts through the era that begins in 1992. Reading this will not offer any major spoilers and it is a suggested read before viewing. The film is still available on Netflix streaming so it catch while you can! If you don’t have a chance to watch it, this article is still worthwhile as a recap of the important moments in modern Italy after the Second World War.

The Italian Miracle

It’s the hot summer of 1966 in Rome and Nicola is taking his final oral exam in medical school before leaving for a summer holiday in northern Europe. After passing the test given in a one-on-one interview by his elderly professor (which is typical in Italy) the conversation drifts to the state of Italy and following exchange takes place.

Professor: “I want to give you some advice. Do you have any ambition? Then leave. Leave Italy while you still can. Whatever you decide go study in London, in Paris, in America if you can. But leave this country. Italy is a country to be destroyed, a beautiful but useless place, destined to die.”

Nicola: “You think there’ll be an apocalypse soon?”

Professor: “I wish! That way we’d all be forced to rebuild. Instead, things here remain immobile with dinosaurs in charge. Leave.”

Nicola: “Then why are you still here?”

Professor: “I’m one of the dinosaurs to be destroyed.”

The back and forth between the old guard of Italy in the character of the professor and the new youth symbolized by Nicola illustrates the divergent mindset each generation has in 1966. The professor had witnessed the rise and fall of fascism, the destruction of his homeland in the Second World War and the wreckage Italy was left with as a result following 1945. The men of Nicola’s generation never experienced the carnage of the 1920’s, 1930’s and early 1940’s. Theirs is an Italy of renewed ambition and optimism without the weight of past mistakes. His was the era of The Italian Miracle.

Italy in 1945 was a country in ruin like much of the rest of Europe. The wage of the average Italian was half what it was when the Second World War had started. The motor from those glamorized Vespa’s that now race around Italian cities were created out of disused airplane starter engines that were abandoned after the fall of fascism. Even in 1950, 5 years after the end of the war, nearly 50% of all Italians households had no kitchen and nearly 75% had no bathroom. Only 7% could proudly state they had running water and electricity. Yet the terrible state of the country would be the setting for one of the most powerful comeback stories Europe had ever seen. Thanks to $1.4 billion in aid through the Marshall Plan that ran from 1948 through 1952, cheap labor through the migration of southern peasants to the urban centers in the north, some of the cheapest energy in Western Europe through natural gas discovered in the Po Valley and lucrative oil deals with the Middle East and the Soviet Union, Italy would witness a renaissance in its economic standing. Between 1951 and 1963 GDP growth in Italy stood at nearly 6% (which was the second best in Europe just behind Germany).

In 1957, the forefather of the European Union was formed with the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC) via the Treaty of Rome. The free trade setup by the EEC created new markets for Italian businesses and by 1965 40% of Italian products were being exported to EEC countries. In 1955 only 3% of households owned refrigerators and only 1% washing machines. By 1975 this number ballooned to 94% owning refrigerators and 76% owning washing machines. In this same year over 66% of Italian households owned a car. The symbol of this new era of the Italian automobile was the FIAT 500, which made the company the largest European car manufacturer by 1967.

This is the Italy Nicola was born into: a country that had a growing sense of optimism in the summer of 1966. The older generation was naturally more skeptical about Italy’s fortune since they have seen this sense of optimism before and it had left them only with a country of ruin. After passing his doctoral exam, Nicola joins his friends speeding around the Aurelian Walls in a FIAT passing a British Jaguar in the process. The future seemed like that same open road winding around Rome.

The Years of Lead

In the winter of 1968 we find Nicola graduated and living with his new girlfriend (Giulia) in Torino. The bleakly grey sky over this northern Italian city is also indicative of the changing mood in the country. The Italian Miracle that had gripped the country in the two decades prior is starting to cool as job prospects dwindle. In what is known as the ‘Iron Triangle’ (which is formed by the northern cities of Genoa, Torino and Milano) low-wage factory workers for the first time in the post-war era realized their power to create changes to labor policy through large collective protests. In what is known as the ‘Hot Autumn of 1969’ industrial workers accrued 440 million hours of strikes across Italy’s urban centers. Many of these strikes are violently repressed by the Italian army and local police forces.

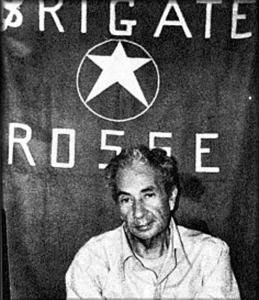

This is this era that Nicola and Giulia find themselves in during the last years of the 1960’s. They participate in occupations of university buildings and fight for the rights of the ‘common man.’ Yet while Nicola is moderate in his ideology and actions, Giulia becomes more radicalized and eventually joins a leftist terrorist group known as the Red Brigades. The era both of them are entering is The Years of Lead where radicalized organizations of both the far right and far left launch terrorist’s attacks throughout the country. It starts with the Piazza Fontana bombing in Milan in which the National Agrarian Bank is attacked in 1969. 17 people were left dead and 88 were wounded. Violence such as this would continue across the 1970’s as both neo-fascist and communist groups vied for national attention. The hope of the previous decades was dwindling, as the national government seemed unable to contain the carnage.

This era was immortalized with the kidnapping of former Prime Minister Aldo Moro on March 16th of 1978 by the Red Brigades. The politician was held for nearly two months in an apartment complex in Rome as the Italian authorities failed to uncover the exact location of the hideout despite searching block by block for days on end. On May 9th of that same spring Moro’s corpse was found in the trunk of a car on Via Caetani. The death of the former Prime Minister angered the nation and citizens questioned if Italy was in a state of moral decay with an inept government. Following Aldo Moro’s demise the government made it a long awaited priority to drive violent extremism from the country. Yet it would be far from an easy task as the bombing of Bologna’s central train station in 1980 by neo-fascist terrorist clearly illustrated. The attack killed 85 people and wounded more than 200. However despite these setbacks the investigation and prosecution of terrorist cells in Italy slowly increased and by 1983, The Years of Lead were at end.

The Fall of the 1st Republic

In the spring of 1992, Nicola (now a practicing psychiatrist) is called on by the judicial system to visit a soon-to-be felon who is caught up in political corruption and bribery. Nicola’s task is to see if his plea of insanity is legitimate. During their conversation, the man looks incredible passive until Nicola brings up family matters. The man replies in the following:

“You work in a hospital, right? I’m sure there are companies that pay you commission. Five, ten percent. That’s standard. I can’t believe you’ve never noticed. Or maybe it did occur to you, but you turned your head the other way, like millions of Italians. One day, a judge arrives and says these commissions are called ‘kickbacks’ and that under-the-table political funding is illegal. Great news! A poor guy who steals an apple isn’t the only one in jail nowadays. Now there’s justice. But they forgot how they used to line up to give us money in exchange for all the favors they asked of us. Now they want to change the world. Believe me, nothing is happening. It’s all fake. They only wanted idiots like me, who got caught. But the others keep stealing, just like before. That’s Italy. I didn’t make it, and neither did you. It’s the Italy our fathers created, believe me.”

The political situation facing Italians in 1992 was a legacy of the country’s politics over the past decades. Prior to the rise of fascism there were three major political currents that ran through Italy: Catholicism, socialism and nationalism. Catholic politics were instilled since 1905 when Pope Pius X allowed practicing Catholics in Italy to go to the polls and exercise their rights as both members of the church and of Italy. The rise of socialist party politics started in the 1890’s when Italy was going through a countrywide recession and banking crisis. Finally, there was the mantel of nationalism, instilled by Giuseppe Garibaldi and the other forefathers of modern Italy. This idea of nationalist politics was later co-opted by Benito Mussolini in the forming his fascist movement. Mussolini would also forge an alliance with Catholic voters as the Lateran Accords of 1929 showed. As well, he greatly suppressed his former socialist party members in political and violent ways.

With the fall of fascism and the nationalist mantra, the two ideologies that survived the Second World War in Italy were Catholicism and socialism. Since socialists were repressed so much during the fascist era, it had a back seat for most of the post-war era to Catholic politics. The party that would hold the new mantel of Catholic politics was the Christian Democracy party. It would rule Italy for the next 50 years.

After the Years of Lead the socialist party made a concerted effort to moderate their political stances. This strategy culminated in the election of Bettino Craxi to the office of Prime Minister between 1983 and 1987. He would be the first and only national leader during Christian Democracy’s reign to demonstrate potential electoral weaknesses in the juggernaut that was the established political party. Yet the rise of socialist forces in Italy would be short lived. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 decimated the socialist political ranks and created an uneasy new world for leftist causes.

With the weakening of a staunch socialist creed, it seemed like it would be smooth sailing for an unfettered Christian Democracy party. This would not be the case. In 1992, an investigation titled Mani Puliti (Clean Hands) would begin and its revelations revealed a huge culture of bribery existing within the halls of parliament. Over half of the parliament was indicted on corruption charges in which political leaders gave and received illicit funds from private bundlers. Many of those indicted later took their own life or were sent to jail. The scandal also spread to local authorities with over 400 city and town councils being dissolved because of damning evidence. At a hearing on the scandal it was revealed that an estimated $4 billion in bribes were exchange by parliamentarians just in the 1980’s. The system, which had kept Italian politics well lubricated for decades, was screeching to a halt.

The Christian Democracy party itself collapsed and was no more. What it left in its place was a power vacuum the size of Italy itself. When the national election of 1994 was announced it was predicted to be the most wide-open contest in the country’s history. When the results rolled in on March 27th a completely new party and former media magnet stepped into the power vacuum and into the halls of parliament. The name and party? Silvio Berlusconi and Forza Italia. The legacy of the Mani Puliti scandal destroyed the old corrupt guard of Italian politics but also created the unstable climate which Silvio Berlusconi has taken a hold of the last two decades. Prime Minister Matteo Renzi who took office earlier this year will do what several politicians have attempted since 1992. Form a cohesive national government without the controlling force of Berlusconi. We are still awaiting a verdict.

So what are we left with in this journey from the summer of 1966 to 2003? Is Italy resigned to its fate put forth by Nicola’s professor and others. That the country is beautiful but fatally flawed? That eras brimming with optimism are only first acts for a second act of despair? When we place our eye for too long under one lens there seems to be no other view. That Italy is place in which its ancient ruins are signs of its ancient accomplishments long since past. Yet, Italy should not be seen in the singular. What The Best of Youth shows is that despite its rocky history the country is made of individuals who are flawed yet earnest, honest and loving. When the prisoner Nicola is interviewing in 1992 states emphatically, “It’s the Italy our fathers created, believe me” a look of conviction comes over Nicola’s face and he shakes his head. He replies, “No, not my father. Believe me.”

I believe him.

1 Comment

Usually I find movies that are really long so boring but The Best Of Youth suprised me because it was interesting I sat through it until the end